Kahnawake, the setting for the “very first” film shot in Quebec

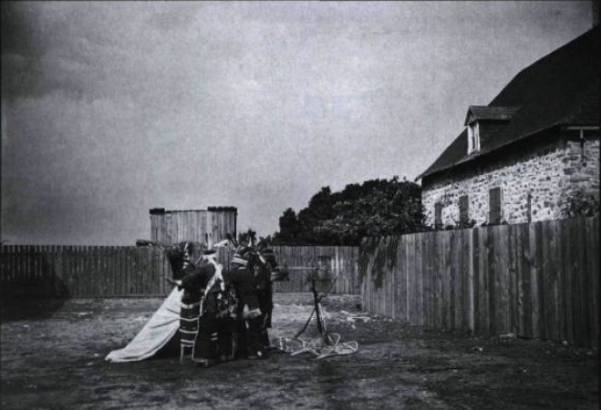

An image from Danse indienne, a copy of which is held by the Cinémathèque québécoise. (Photo: Domaine public)

Danse indienne is a silent film of just 50 seconds, made in 1898 by Gabriel Veyre, an operator with the Lumière brothers. Filmed in Kahnawake, it is believed to be the first film shot in Quebec, or at least the earliest that has been found.

Translation Amanda Bennett

The motionless camera pans across a teepee, showing three natives dancing in traditional garb, wearing feathers on their heads.

To mark the 100th anniversary of cinema in 1995, funds were made available to restore films in Lyon, where the brothers' factory was located. Among the works unearthed was this “Danse indienne”, by Gabriel Veyre who was a “commis voyageur” operator, travelling the world to bring back images.

“At first, they believed it was Indians from India, because Veyre had travelled all over South America, then all over America, before returning to France,” explained André Dudemaine, founder of Terres en vues, the organization behind Montreal's First Peoples' Festival.

Speculation then turned to Canada, where Veyre had spent time. It was at that juncture that André Gaudreault and Germain Lacasse, two specialists in early cinema at the Université de Montréal, were approached.

Their research showed, as reported in an article in the spring 1995 issue of 24 images magazine, that Veyre would have presented several views to the cinematograph during his stay in the country. Danse indienne could have been shot on September 2 or 3, 1898. In Canada, he ventured only to Quebec and Niagara Falls.

The quest for a location

Mr. Lacasse and Mr. Gaudreault called on André Dudemaine to try and trace the exact location of this short film. Photographs from the set, showing more of the scenery, were helpful.

“All we could see was a fragment of a building that could be from the French colonial era. So I set out to find it,” detailed Mr. Dudemaine.

He contacted Michael Loft of the Mohawk Cultural Centre of Kahnawake. Loft thought the building looked very similar to what used to be a rectory and is now the Kateri Tekakwitha Shrine. But in the photo, the building had two dormer windows, not three like the one he knew. It was a Jesuit by the name of Louis Cyr who solved the puzzle. He recognized the site, next to the old cartouchière of Fort Saint-Louis. The third skylight had been added after the fact.

The building that identified the filming location. (Photo: Domaine public)

A colonial and folkloric look

The next step was to find out who was in the images. Back at the Mohawk Cultural Centre, a man on site, a Mr. Philipps, saw the photos and recognized his grandfather.

Mr. Philipps' grandson also made it clear that this little dance was in fact a staged event for the tourists who came to Kahnawake.

The communities were open, for economic reasons, to making a few concessions and participating in this folklorization of the “pure Indian” who lives according to his traditions explained André Dudemaine, a member of the Mashteuiatsh community.

In the light of today's ethics, however, the Lumières brothers' film has the flaw of showing this antiquated representation as reality.

Germain Lacasse doesn't hesitate to speak of the Lumière brothers' colonial approach. "Operators like Veyre were on a mission to travel the world in search of exotic images. Colonial France made the world its own! It's a lot of clichés.”

The inscription “Canada's last Indian village” on the back of one of these photographs contributes to this perception.

It's very much in the spirit of the times,” Mr. Dudemaine went on. The Lumière brothers weren't artists, they were merchants.”

One of the set photographs (Photo: Domaine public)

But they weren't the only ones filming in Quebec. In 1897, Edison operators had come, as had Ernest Ouimet, who made dozens of films in Montreal from 1906 to 1922.

Kahnawake also featured in Dollard des Ormeaux, 1913, made by an American-Canadian company. Kahnawake residents were extras in the film.

Danse indienne was not shown to the Indigenous community until 1995, at the First Peoples' Festival.

The Philipps family was very happy to see it,” noted Mr. Dudemaine. I think it was received with curiosity and kindness. We recognized that it was from another era.”