Flood zone : Dikes to be recognized

On the banks of the Châteauguay River, a mound acts as a dike. (Photo: Le Soleil –Denis Germain)

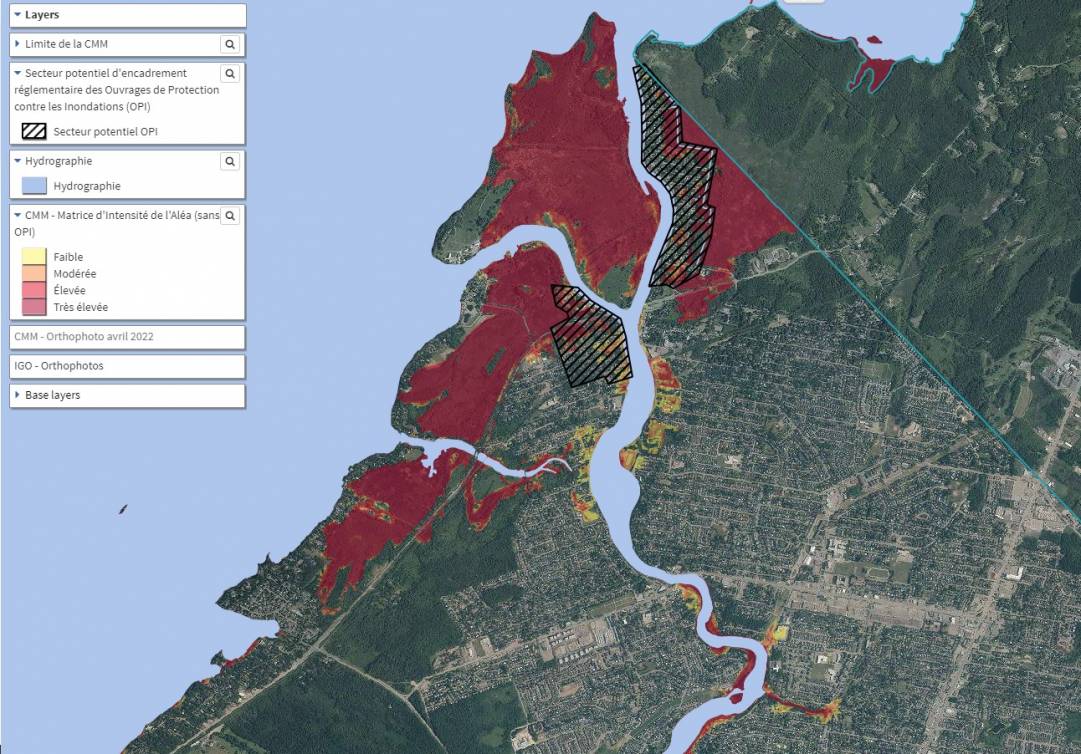

In the new preliminary map of flood-prone areas published by the Communauté métropolitaine de Montréal (CMM), some 400 Châteauguay residences are in flood-prone zones, even though they are protected by dikes. The City of Châteauguay, like other municipalities in Quebec, is asking the provincial government to quickly recognize the utility of these structures to avoid significant consequences for homeowners living in these areas.

Translation Amanda Bennett

The Quebec government is in the process of modernizing its regulatory framework for water environments and flood-prone areas. The new preliminary map has been produced by the CMM to inform municipalities and citizens, and “allows them to visualize the impact of the regulatory proposal on their territory”. It takes into account the floods of 2017, 2019 and 2023, as well as the anticipated effect of climate change. In many cities, this means that a significant number of homes will now be included in the flood zone.

The new CMM map. The striped areas represent the dyke sectors. (Photo: screen capture)

For Châteauguay, the number of residences in a flood zone would rise from 700 to 1100, according to Mayor Eric Allard, because the dikes on Salaberry Nord and D'Youville boulevards are not recognized as “protective structures”.

“For these works to be considered, there are a series of criteria that must be met, and the Municipality will have to take responsibility for them,” explained Brent Edwards, team leader at the CMM's Flood Risk Management Project Office. The Ministry of the Environment will approve the works.

Avoiding the yo-yo effect

In its brief, the CMM points out that this approach generates concern for people living near the structures. “We have to avoid a situation where people temporarily find themselves in a high-risk zone, and then a year or two later, once the government has approved the whole thing, we switch everyone to a low-risk zone. We have to avoid this kind of yo-yo,” explained Mr. Edwards.

Châteauguay's mayor agrees. “If we put up dikes and maintain them, it's safe. There's no reason why they shouldn't be recognized,” said Mr. Allard in an interview. The Mayor assured us that the dikes in the municipality are well maintained. “We've undertaken maintenance compliance work on the dike. We're there because we found a small breach where there was a bit of runoff. It has been repaired,” he said.

Previously, flood zones were classified according to high current (0-20 year zone) and low current (20-100 year zone). The former meant that there was a 5% chance of being flooded every year, while the latter represented a 1% risk. In the new regulations, there will be four zones ranging from low to very high.

Climate change is also factored into the new calculations. Mr. Edwards cites the example of Lac Saint-Louis, whose water level is controlled by the dam at Cornwall. “There haven't been any major floods since the 1970s in Lac Saint-Louis thanks to this management, but for the future, with climate change, there's going to be more water, more extreme events, it's possible that this management won't be adequate to manage all this water,” he explained.